Inadvertent Prudent Technical Debt

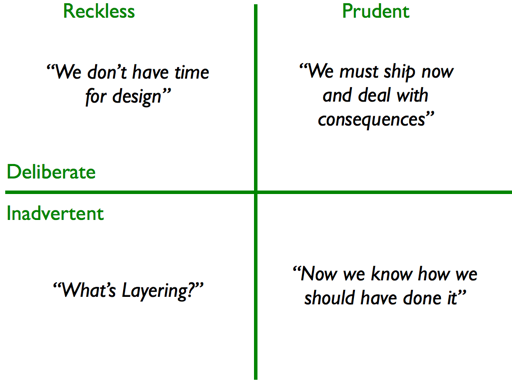

I recently stumbled upon a great talk by Martin Flower about Technical Debt.1 In the talk, he first classifies technical debt according to whether you are aware of taking it up (deliberate) or not (inadvertent). Then he also classifies it according to whether you do so as the result of an informed decision (prudent) or because you don’t care (reckless). From these two dimensions Martin forms a classification, separating four categories of technical debt:

A Classification of Technical Debt by Martin Flower

What struck me most, is the notion of inadvertent prudent technical debt, i.e., debt that we take on unknowingly, even though we do our best to avoid it. In other words, this is the kind of debt we take on, because we don’t (yet) know enough about the problem at hand in order to see the better alternatives for solving it. Whenever you find yourself thinking “oh my, I should’ve done it this other way,” you’ve discover a piece of technical debt that falls into this category.

Now the interesting thing about inadvertent prudent technical debt is that we cannot avoid taking it on, because we do so inadvertently. It’s even possible that we take it on by making a well-informed, perfectly-sensible decision that becomes problematic only in the light of aspects of the problem that we couldn’t possibly foresee (given what we knew at the time). This implies that our code base always contains some sleeping debt that may jump at us at any time.

The problem about technical debt is that it slows down development. It stands between us and new features. It stands between us and change. Or, as Martin Fowler and Rachel Laycock put it: You can’t be agile when you’re waist deep in mud. I find it difficult to teach this, especially because present bias seems to drive many students to frequently take on deliberate reckless technical debt. Someone who’s never experienced the effects of technical debt in the long run is especially likely to underestimate its cost. Maybe this is one of those effects everybody needs to experience for oneself, before starting to take it seriously.2

Considering that there’s always an unknown amount of debt lurking in our code base, we should be extra careful to take up additional debt deliberately. We should never do so recklessly, and when taking some debt on prudently, e.g., because of a deadline next week, we should immediately reserve time to deal with it after the deadline. As for inadvertent prudent technical debt: there’s really nothing we can do to prevent it. Hence, we need to train ourselves to be prepared when we face it. The Agile Fluency Model by James Shore and Diana Larsen is an interesting concept that might lead the way. Deliberate Practice is probably what it takes. What do you think?

-

In case you haven’t listened to any of his, I recommend you to do so, because it’s always fun and instructive. ↩

-

I made this experience during my Master’s, when I participate in a one-year software engineering project with a customer from industry. After about nine month, we came to feel the effects of our initial design decisions (and those we failed to make). I believe that one-semester labs are most likely to short to experience this. ↩